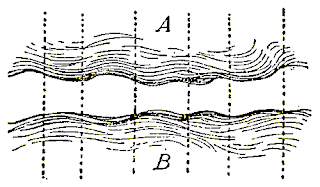

Martin (2013: 5):

… both terms involved in the linguistic sign are psychological and are united in the brain by an associative bond. This point must be emphasised.

Moreover, the terms signified and signifier are mutually defining — the valeur of each is its relation to the other — so each presupposes the other, as Hjelmslev (1961: 48-9) notes for content and expression:

Expression and content are solidary — they necessarily presuppose each other. An expression is expression only by virtue of being an expression of a content, and a content is content only by virtue of being a content of an expression.

[2] To be clear, the diagram misrepresents Hjelmslev's distinctions in two important ways. First, like the previous diagram, it misrepresents Hjelmslev's (and SFL's) content and expression planes as the strata of lexicogrammar and phonology. Second, it misrepresents content substance (thought) and expression substance (sound chain) as sharing the same domain and level, despite the former being psychological and the latter physical. Hjelmslev (1961: 58):

The sign is a two-sided entity, with a Janus-like perspective in two directions, and with effect in two respects: “outwards” toward the expression-substance and “inwards” toward the content-substance.